The past few weeks have been filled with a variety of news stories with varying degrees of coverage. From the earthquakes shaking the cities of Turkey and Syria to the derailed train leaking toxic chemicals in Ohio, there has been a noticeable surge of stories, all of which were happening during the week of the Super Bowl.

With so many world events happening in tandem, I started to see an interesting pattern. It seems that with so many stories to follow, people’s attention had been split between them. I heard friends and classmates commenting on the major stories, and then wondering why there seemed to be a lack of coverage for one or another. And this got me thinking. What was the appropriate amount of coverage for any of these news stories? Should the daily earthquake rescues be overshadowed by the growing contamination of Ohio? Would it make sense for both stories to take a backseat in order to highlight some good ole American Football?

And more importantly, do the news outlets covering these stories have an opinion on which events deserve more time in the spotlight? The news stories we see and the rate at which we see them is a vital aspect of modern society. It can sway elections, drive consumer choices, and overall change public opinion. A very powerful tool to be wielded by private corporations, even those who claim to promote journalistic integrity.

Photo from Carnegie Melon University

Photo from the New York Times

So after some research on the topic I discovered a way of conceptualizing this phenomenon. “The Attention Economy” is a term coined by political scientist Herbert A. Simon, and was later popularized by author and former theoretical physicist Michael Goldhaber in the late 90s. Goldhaber used this term to describe the global competition for what he calls one of the most finite resources in the world: human attention. With the age of the internet fundamentally changing the way we access and spread information, Goldhaber saw a new frontier being rapidly uncovered. With access to all of the information in the world at the tap of a finger, what determines what we actually pay attention to? The attention economy has one simple answer: money.

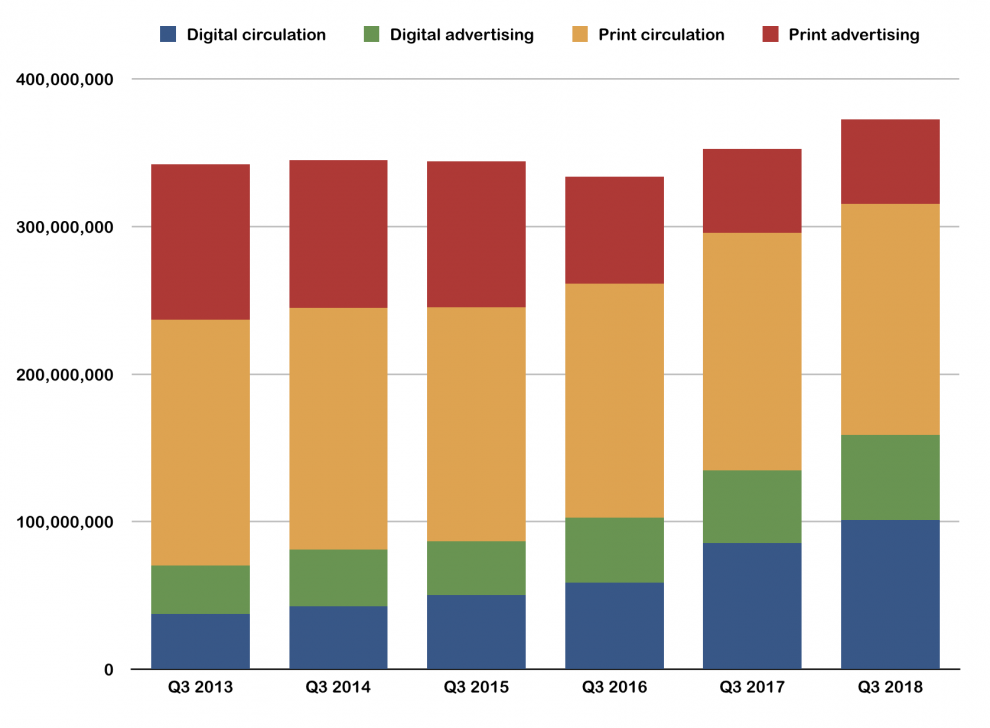

Goldhaber had glimpsed the first few signs of the revenue landscape we live in today. Print media was disappearing, replaced by digital content that could be reproduced and spread with just a few clicks. The attention economy had existed before the internet, as attention has always been associated with power and influence, but the internet completely redefined the way we monetize attention. Instead of newspaper sales, ads would ensure that news outlets could make money off of their audience. But ads produce far less revenue per view than the purchase of a newspaper, leading to lower profits overall for competing news outlets. So news as a whole was forced to adapt to its new landscape, maximizing attention above all else. Goldhaber predicted this in an 1997 Wired article, stating “As the Net becomes an increasingly strong presence in the overall economy, the flow of attention will not only anticipate the flow of money, but eventually replace it altogether.” In modern advertising the flow of attention has effectively superseded the flow of money, as whichever site has the most viewers will also generate the most revenue.

Additionally, news outlets like the New York Times and Washington post have had to heavily on the use of sites like Facebook to spread their content. With 29% of Americans getting their news from Facebook, it has become an invaluable tool for spreading stories. People don’t scour the web looking for news articles, they simply accept what is put in front of them. Whether this comes in the form of a Facebook post or Instagram link, news outlets will be there to grab all the clicks that they can.

But this also makes their content subject to the algorithms that run these social media sites. News outlets must adapt and change their style to make better use of these algorithms in order to be recommended to more people. This leads to more extreme, eye catching headlines that may bend the truth to sensationalize an event, a trend that has only continued to plague social media sites as the fight for clicks gets even more competitive.

Graphic by Nieman Labs.

So how does this impact which stories are prioritized by news outlets? Well, stories that are more attention grabbing become more valuable, regardless of their actual importance. This simple fact has changed so much of the world already. The information we consume dictates our values, the choices we make, and the context in which we make them.

A great example of this change in context is the idea of the Overton Window. In politics, the Overton Window is essentially a way of identifying the range of governmental policies the public will accept. For something like an election, the Overton Window could determine what behavior a candidate could exhibit while still being viewed as a favorable choice. Anything outside of the Overton Window would be seen as politically incorrect and not befitting of a governmental candidate.

But the Overton Window is not static. It can be shifted as public opinion changes and makes things that would otherwise be seen as “politically incorrect” a normal aspect of politics. The 2016 US election is the perfect example of a clear shift in the Overton Window, as many behaviors Donald Trump exhibited during his candidacy were unprecedented for a politician in his position, and yet seemed to be championed by his followers. In fact, rather than hurting his campaign, the many controversies may have actually propelled his way to the presidency.

Living in the digital age of news, it is easy to spot some of the human patterns of attention. For example, controversy always seems to be easily spread, and stories provoking outrage make up some of the biggest headlines. Election cycles make for interesting case studies on this topic, outweighing all else in terms of viewership, likely because the news stories concerning political figures have a direct impact on public opinion and the eventual outcome of an election.

So when a candidate known for provoking outrage and being a controversial figure enters the mix, naturally their subsequent news stories, good or bad, rise to the top and suck up the most attention. To follow Goldhaber’s reasoning: “When you have attention, you have power, and some people will try and succeed in getting huge amounts of attention, and they would not use it in equal or positive ways.” Even back in 1997 the first seeds of the modern age were clear to Goldhaber, and events followed as such. Controversy ruled supreme, the Overton Window widened, and Donald Trump won the 2016 election.

“When you have attention, you have power, and some people will try and succeed in getting huge amounts of attention, and they would not use it in equal or positive ways.”Michael Goldhaber, 1997 WIRED

So what is the appropriate amount of coverage for any given news story? The answer is unclear, but also somewhat irrelevant. The minutiae of our attention dictates the amount of coverage news stories receive, for better or worse. Corporations will follow the money and promote content that will garner the most attention. These past few news cycles have shown that our attention is limited, and some stories will fall through the cracks.

Unfortunately, the solution is far from sight. Modern journalism is a zero-sum game, and if news outlets tried to be more conscious of the attention economy and its potential downsides, they would lose their viewers to outlets that lack the same integrity. So attention remains a top priority, warping and shifting the sociopolitical landscape in known and unknown ways. The future shape of journalism remains to be seen, but the attention economy will undoubtedly remain a factor in the global flow of information for the foreseeable future.