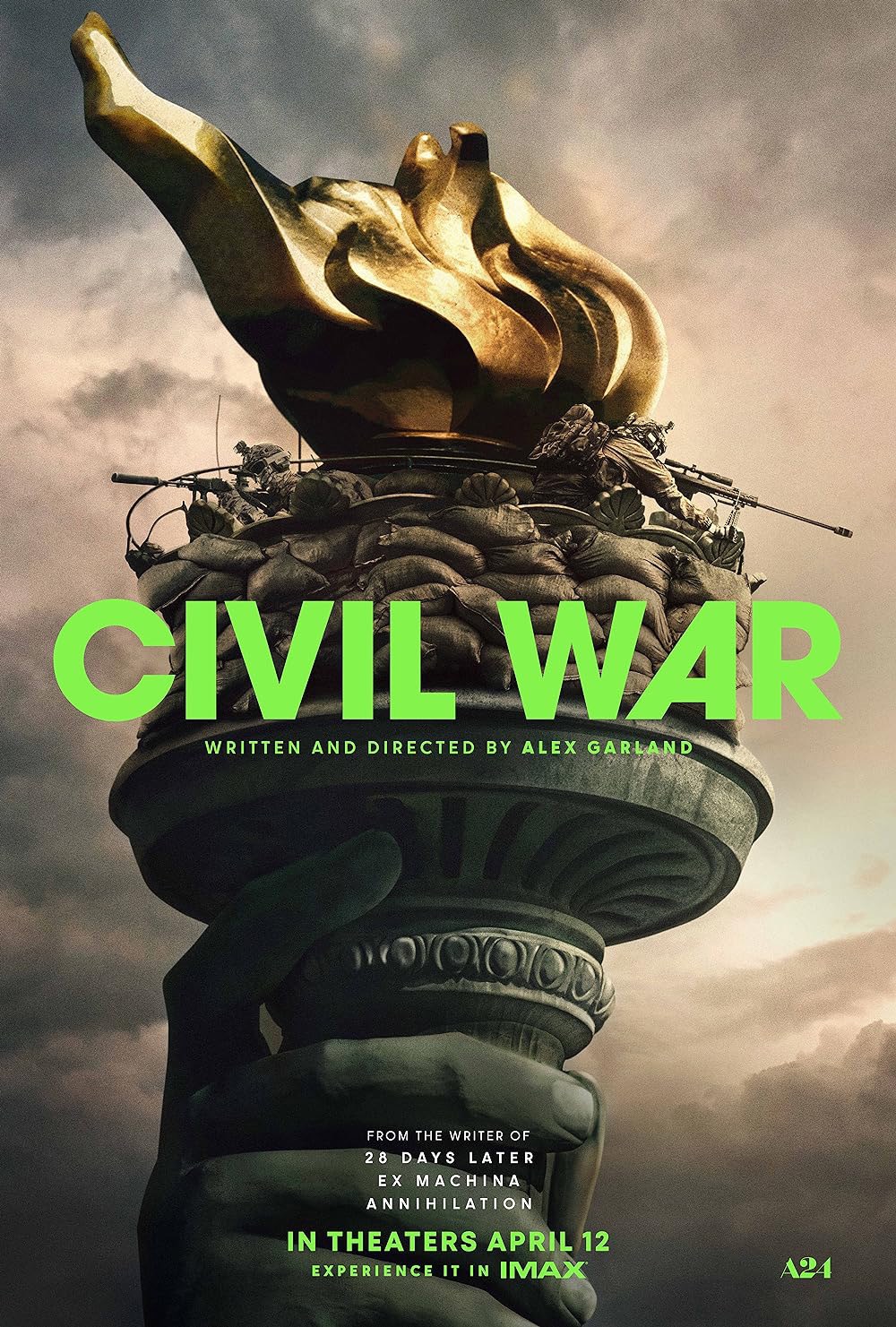

I saw Alex Garland’s Civil War with my friends because the movie seemed like an entertaining, if self-serious warning about how America could descend into a civil war. The trailer featured cool shots of the White House getting blown up, and as Vulture film critic Bilge Ebiri said in his review “Americans sure do love to see their institutions destroyed on screen.”

Civil War was not that movie— what the trailer and press junket failed to relay is that Civil War is not a movie about polarization in America but about the nature of political violence, violent imagery and the moral tradeoffs of war photography. The film does deliver in its depictions of American institutions getting destroyed on screen, but examines why audiences want to see that.

Civil War begins at the end of the titular affair, as a fascist president played by Nick Offerman is about to surrender to the Western Forces, an inexplicable alliance between Texas and California. There are also several other factions of Americans fighting each other, such as the Florida Alliance. In this setting, we follow hardened photojournalist Lee Smith, played by the absolutely incredible Kirsten Dunst, fellow war reporter Joel, and veteran journalist Sammy working for Reuters and “what’s left of the New York Times.” Along the way, they pick up Jessie, a wannabe photojournalist that idolizes Lee, and convinces Joel to let her tag along after Lee saves her from a protest that got out of hand in wartorn Brooklyn. They began their road trip from New York to DC in order to get an interview and photo with the president before he surrenders and is killed by the Western Forces.

As they make their way south, they encounter truly horrendous visions of what war actually looks like: two men strung up, still alive and being tortured in an abandoned car wash, mass graves, refugee camps, suicide bombings. At every turn people are shot point blank and horrific poverty abounds. The violence is at once nonsensical and calculated, and Lee and Jessie capture it all without hesitation or sense of emotion to their subjects.

Civil War shows its protagonist reporters to be professionals deeply dedicated to their mission, but it also doesn’t turn a blind eye to the fact that at the end of the day, in the midst of endless suffering, Lee and Jessie still want a good photo. It is undeniable that photojournalists are needed in combat zones to capture the reality of the violence we inflict on each other. But Civil War also suggests that the person capturing that violence, even if it is for the good of the public, runs the risk of diminishing the humanity of the subject. In the car wash scene, Lee poses the torturer with his victims when she takes their photo, when Jessie shows her an image she took of a soldier taking his dying breath, she responds by praising the composition of the shot.

What it means to capture and consume violent imagery has never been more relevant. Going on your phone or turning on your television means that you may see someone dying in a mass shooting or terrorist attack or police killing. Videos of George Floyd being murdered, photos of Abu Ghraib torture victims, of the 9/11 falling man, these are just a few examples, all of which propelled people to action. But also, on some level it is profoundly unsettling, that the existence of those photos and videos means that someone, somewhere, saw death or suffering and then captured it on camera to show others.

The Washington Post ran a series in November titled “Terror on Repeat,” which featured graphic images of mass shootings done by gunmen wielding AR-15s. In doing so, it broke an unwritten media rule that bloody photos of mass shootings should not be published in mainstream news outlets. The executive editor of The Washington Post defended their decision to run the pictures, saying that doing so advanced the public good because “most Americans have no way to understand the full scope of an AR-15’s destructive power or the extent of the trauma inflicted on victims, survivors and first responders when a shooter uses this weapon on people.” There is an argument to be made that it’s time that the American public sees up close and personal the consequences of our politicians voting again and again not to restrict the sale of guns. As journalism professor Susan Linfield said in a New York Times opinion piece about the issue, perhaps “the nation should see exactly how an assault rifle pulverizes the body of a 10-year-old.”

Most of the parts of Civil War that are striking are so because they are familiar. Images of Ferguson in 2014, of the Black Lives Matter Protests of 2020, of bodies strewn on the ground after a gunman in a mall or music festival or elementary school or church opened fire all echo the political unrest and violence that we see in movies like Civil War. What Civil War does differently is that it forces the viewer to see that we don’t have to wonder what it would be like to see contemporary America as a war zone—we already know.