(Note: This article was written before the Sutherland Springs, Texas church shooting.)

On Oct. 1, 2017, the deadliest mass shooting in modern United States history was committed by 64-year-old Stephen Paddock. There was no apparent motive behind the attack, the only explanation being that Paddock was mentally deranged.

This has led to an important debate of how to end gun violence and gun crime in America. Nobody can argue that gun deaths are a good thing, so we can all agree that reducing gun deaths is a pressing contemporary issue. We just disagree on how to achieve this end.

The bipartisan condemnation of bump-fire stocks, which, for all intents and purposes, allow a stationary shooter to convert a semi-automatic rifle into a functionally fully-automatic one, is a good step forward. However, the banning or imposing of tax stamps upon bump-stocks won’t keep Americans from being killed by someone with a gun.

On average, approximately 33,000 Americans are killed by individuals with guns every year. As Leah Libresco, a former Five Thirty-Eight analyst, notes in her Oct. 3 Washington Post op-ed, nearly two-thirds of gun deaths are suicides, approximately one in five deaths are due to gang and street violence and another 1,700 deaths (approximately 5%) are women killed in instances of domestic abuse.

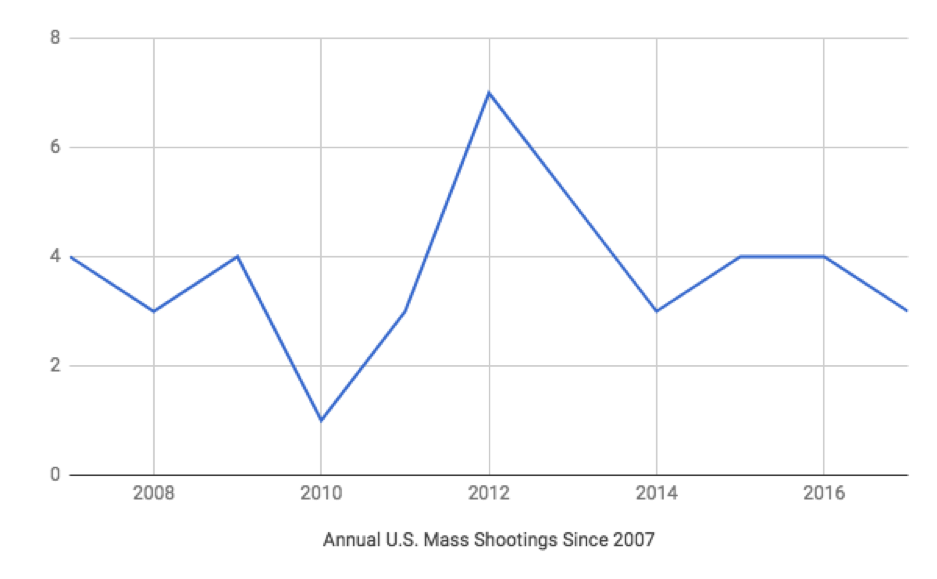

Together, these three categories comprise almost 90% of the annual gun deaths in the United States, yet we only focus on mass shootings, which, according to Five Thirty-Eight and the FBI, account for fewer than 0.2% of annual gun deaths. Not only are few Americans killed in mass shootings (65 in 2016), defined by the FBI as any shooting in which four or more people excluding the shooter were killed, but few are killed with “assault rifles” (which is a term fabricated by Senator Dianne Feinstein in the 1980s, having no functioning definition other than a “scary, military-esque” rifle; in 1991, the New Jersey Law Review, in collaboration with U.S. Army weapons specialists, defined an assault rifle as being fully-automatic). According to the FBI’s 2016 Unified Crime Report, the most common type of gun used to kill Americans is a handgun (7,105 handgun murders out of 11,004 total firearm murders in 2016) while rifles of all kinds are used to kill only 374 Americans.

Moreover, Libresco and her team at Five Thirty-Eight find that banning suppressors and large magazines have no statistically significant reduction on the number of people killed with those attachments. Libresco notes in her op-ed that many gun-control advocates are uninformed, misleading or outright deceptive about the effect a suppressor has on the volume of a gun’s rapport, finding that an “AR-15 with a silencer is about as loud as a jackhammer.” In addition, a magazine’s size is irrelevant, as “a practiced shooter could still change magazines so fast as to make the limit meaningless.”

This only goes to show that most (or at the very least, the most visible) gun control advocates are woefully disconnected from reality.

In order to reduce gun deaths in America, we need to be practical. We can’t ban all guns (District of Columbia v. Heller 554 U.S. 570 (2008)), nor can we ban handguns, the most common type of firearm used in gun deaths (McDonald v. Chicago 561 U.S. 742 (2010)). From a policy perspective, the best ways to reduce gun deaths in the U.S. are to improve mental health treatment, to crack down on street gangs and to enact more proactive laws while enforcing existing ones that prohibit domestic abusers from obtaining guns.

On an annual average, suicides approximate two-thirds of all gun deaths in America. Worst of all, suicide rates have been rising in the United States for several decades. While the New York Times notes in April 2016 that the proportion of suicides by gun has actually been decreasing, total suicides by every method have been steadily increasing since the 1990s. This is especially true for middle-aged men between 35 and 64 years old, who have seen an increased suicide rate of nearly 50% between 1999 and 2014.

Suicide is a national pandemic. According to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, approximately 44,000 Americans commit suicide every year. Yet in spite of this, the National Institute of Health was appropriated only $25 million in 2016 for suicide prevention programs. What may have the largest impact on gun deaths is to increase federal funding for suicide prevention by at least threefold (this is an arbitrary number; I was unable to find a recommended level of funding).

The second largest cause of gun deaths in America is what Libresco describes as street and gang violence. A vast majority of the roughly 6,600 Americans killed in street/gang violence are young black and Latino men in urban areas. Since 2015, we have seen a relatively sharp spike in the urban murder rate. This correlates with (though is not necessarily a causal relationship) Pew Research Center finding that 72% of police officers are less reluctant to approach suspicious-looking individuals and that 76% are less likely to use force when it is appropriate in light of recent high-profile shootings of unarmed black men.

This straddles a fine line between proactive policing and racial profiling. To be sure, I am in no way advocating for racial profiling; every American, regardless of ethnicity, deserves their right of presumptive innocence until guilt could be proven. This is one of the core tenets of a civil society, but we are faced with a 0.6% increase in the overall U.S. murder rate and a 20.4% increase in the urban murder rate between 2015 and 2016, according to the FBI. We do need to hold officers accountable for their unjust actions, but they in turn should not face unjust criticism for simply doing their jobs by “walking the beat.” Proactive policing, not racial profiling, is the best way to reduce street/gang murders, as officers cannot prevent crime if they are not there to see it occur.

Finally, the third largest category of victims murdered with guns is comprised of women killed in situations of domestic abuse. We have already taken action to prevent domestic abusers from owning firearms: the Lautenberg Amendment to the 1968 appropriations bill prohibits domestic abusers from purchasing firearms.

But it doesn’t go far enough.

The Lautenberg Amendment does not address domestic abuse between non-spouses and does not require offenders to surrender their previously-owned firearms after they have been convicted of domestic abuse. The Lautenberg Amendment also does not require states to report domestic abusers to the federal government. At the very least, the amendment should be expanded to protect all dependents from abuse by requiring convicted domestic abusers to surrender their previously-owned firearms. The FBI should also require all states to report convicted domestic abusers to the federal body responsible for conducting gun purchase background checks.

Gun deaths are a pressing contemporary issue. While it may be true that some deaths are the unfortunate price of the liberty to own guns, there are far too many people whose deaths could be prevented if we implemented a handful of target-specific policies without violating the Constitution.

Mental health background checks, while a novel idea, would only be effective for screening the currently mentally ill. They would do nothing to keep guns out of the hands of those who experience a deterioration in their mental health after they have passed the background check.

Banning attachments to guns won’t reduce the number of deaths, as making the gun look more scary doesn’t make it more deadly. Furthermore, banning “assault rifles” won’t accomplish a reduction in gun deaths or murders, as “scary-looking” semi-automatic rifles are rarely used in shootings, especially mass shootings (when using the actual definition of mass shooting, only seven of the thirty mass shooters–or 23%–since 2010 have used “assault rifles,” according to Mother Jones).

Moreover, disliking guns isn’t a legitimate argument for banning them. Just because you might not like guns doesn’t give you the right to take away others’ liberty; I don’t like flag burning, but I’m not screaming for a constitutional amendment that would curb others’ freedom of speech.

The best ways to reduce gun deaths are to focus on preventing suicide, to crack down on street/gang crime and to keep and take guns out of the hands of domestic abusers. We have empirics which show that we can significantly reduce the number of unnecessary deaths without violating the Constitution. Instead of grandstanding for useless laws or being near criminally complacent, why don’t we do something that will work?