It may seem ridiculous now, but before our digital age of streaming and the internet, media used to exist in a physical format. Sure, you remember your parent’s CD collection, or an old VHS player with their clunky tapes. And for those audiophiles out there, you may even have a vintage vinyl collection that you praise for its superior audio quality, when even audio experts can’t really tell the difference.

Hidden amongst these successful media formats, the ones that stood the test of time and memory, are dozens of failed ventures, lost formats that served as stepping stones to greater endeavors. Here, we will unearth these buried vestiges of an analog world, find out what they did well and why they died, before finally putting them to rest.

Our working definition of dead media comes from author Bruce Sterling, who started the Dead Media Project in 1995. Media is “a device that transfers a message between human beings,” and dead media is such a device that is no longer manufactured or used in any mainstream capacity.

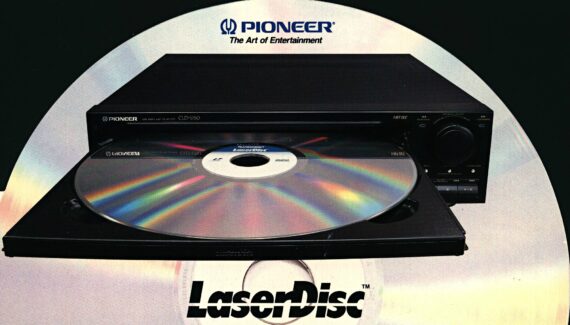

The LaserDisc

Photo by The Pioneer Corporation.

The Laserdisc is our first piece of dead media, released in the US in 1978 as a home video format called DiscoVision (groovy, right?). Each LaserDisc looks like a vinyl record-sized DVD and could carry up to 64 minutes of video on each side. I actually own a LaserDisc that I found in a thrift store underneath a pile of records. It’s a special edition of the 1985 movie “Brazil,” (which I would highly recommend if you are into unusual sci-fi stories with ingenious practical effects.) Anyway, despite predating the DVD by about 20 years, the LaserDisc offered high-definition video, almost doubling the resolution of VHS, its contemporary competitor.

The unique format of Laserdisc also allowed for special features like freeze frame, variable slow motion, and reverse play, something other formats did not fully support. The freeze frame function could even reference each frame of a film by number, which made it very popular in film schools and similar analytic settings.

The technology behind LaserDisc is called optical video recording, invented by David Paul Gregg and James Russell in 1963. At a basic level, it is an analog format consisting of small holes embedded in the disc surface to be read by the player’s laser. This hole, no hole sequence (also called pits and lands) was interpreted by the player and played back as video.

As for the death of the LaserDisc, there are multiple causes. For one, the players were expensive and unable to record TV broadcasts, which was a large draw for VHS. Its superior quality was only truly appreciated by videophiles and playback errors like crosstalk made it a less attractive alternative to VHS.

Despite its popularity in Japan and other wealthy Southeast Asian countries, LaserDisc never took off in the US. The last film on LaserDisc was released in Japan on September 21st of 2001, marking its death.

LaserDisc, we lay you to rest. Rest in Peace, 1978 – September 21, 2001.

DIVX

Photo by ProScan

Our next dead media format is an unusual one. Created by Circuit City in 1998 this format was marketed as an answer to DVD rentals, the words “no returns, no late fees” rampant in its marketing. Called DIVX (Digital Video Express) the format was essentially a specialized DVD with additional encryption and DRM (digital rights management) to ensure that discs could only be played at certain times. Every disc was initially playable for 48 hours after purchase, after which you could call the company to add more time to your rental. When that period was up, you were encouraged to recycle or discard the unplayable disc.

There was also a feature called DIVX silver, where you could upgrade a normal DIVX disc by calling in and paying a larger fee.

The technology of the discs relied on unique barcodes embedded within them that told specialized DVD players with DIVX technology if the disc was playable or not.

As you can expect, there was huge public pushback against this format. Environmental concerns were brought up and DVD retailers attacked the format for being anti-consumer and overly restrictive, calling DVD an “open format” in response.

Despite this, for a time DIVX was a popular format for new releases. Studios valued its stronger encryption, namely Dreamworks, 20th Century Fox, and Paramount Pictures, who all released new films exclusively on the DIVX format for a short time after its release.

Similar to the other dead formats mentioned, the DIVX player was expensive, almost twice the price of a normal DVD player at release. This is speculation, but I doubt many people wanted to pay even more for a restrictive format that required a phone call to unlock your discs.

DIVX died a year after its release, on June 16, 1999, when the format was officially discontinued, hastening the decline of Circuit City.

We lay you to rest DIVX, and good riddance to your DRM.

Rest in Peace, June 8, 1998 – June 16, 1999.

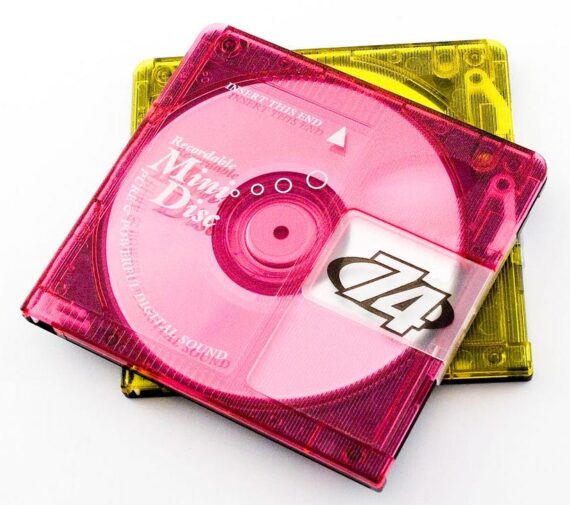

The MiniDisc

Photo by Peter Huys on FreeImages

The last format is a personal favorite of mine, mainly due to its compact design and retro-futurist style. The MiniDisc is just that, a small, CD-like disc encased in a permanent plastic covering. They look like a cross between floppy discs and CDs, and function similarly as well. Released by Sony in November of 1992, the MiniDisc was a portable, recordable, compact response to the cassette tape. The Walkman had dominated the 80s, and now Sony gambled on a new future for the 90s.

Not only was the MiniDisc re-recordable, up to “a million times” as claimed by Sony, but its high read speed also allowed for gapless playback, a feature that eliminated audio skipping. It came in 60-minute, 74-minute, and 80-minute variations, matching the capacity of CDs, though in a lossy, compressed format called ATRAC (Adaptive Transform Acoustic Coding).

Discs were recorded using a laser and magnetic field, called a magneto-optical system. The laser would heat the disc until it was able to be manipulated by the magnetic field, which recorded digital data by altering the polarity of the disc in a readable pattern.

But alas, the MiniDisc never fully took off. CDs were rising as the most popular medium for music, and despite its unique design, few record labels embraced the format. This, along with the expensive costs of an entirely new player, was a tough sell for the teenage market.

Despite surviving for about almost two decades, the MiniDisc was discontinued in March of 2013. Rest in Peace, November 1992 – March 2013.

And rest in peace to all of the lost discs, floppy or not. We may not use the formats of old but they still serve as worthwhile markers in our species’ technological advancement. Streaming may be the next big thing, but who knows what format will come along and overtake it. Only time will tell.